Narrating a People’s History of 1971

A review of Anam Zakaria’s 1971: A People’s History from Bangladesh, Pakistan and India

A year that decidedly marked the relationship between India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, 1971 has come to represent different political symbols for each of those countries. For Bangladesh, 1971 was the year of its liberation from Pakistani occupation after a brutal nine-month-long war and genocide; for Pakistan, 1971 represents the “fall of Dhaka”, a tragic moment in its history that was preventable and marked by betrayal; and for India, 1971 represents the year of its victory against Pakistan and its emergence as the hegemonic powerhouse of the subcontinent. Scholarship on 1971 often reflects these contradictory nationalist narratives.

Most recently, Sarmila Bose’s widely discredited (most exceptionally by Nayanika Mookherjee) Dead Reckoning attempted to rebuke all accounts of a “genocide” in East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) and instead portrays Pakistani soldiers as gentle victims of attacks from Bangladeshis. Bose provides future scholars with a spectacular example of how not to approach the topic of 1971. To her credit, Bose did highlight the degree to which the Pakistani state’s “forgetting” of 1971 has resulted in a collective remembering of the violence as being perpetrated by the other side.

Yasmin Saikia’s Women, War, and the Making of Bangladesh: Fragments of 1971 and Nayanika Mookherjee’s The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories and the Bangladesh War of 1971 offer a different and more relevant perspective. They bring out the narratives of victims of sexual violence, whose experience had been appropriated by the Bangladeshi state to serve its own ends. Works such as these counter and add to the state-based approach of texts such as Srinath Raghavan’s A Global History of 1971 and Gary J. Bass’s The Blood Telegram.

Inheriting the heavy baggage that comes with this field of study, Anam Zakaria’s 1971: A People’s History from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh takes up the task of exploring the narratives of 1971 from the perspective of citizens of India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. The bulk of this text consists of interviews with a range of people: the Biharis “left-behind” in Bangladesh, women who faced sexual violence during the war (known as Birangonas), Bangladeshi activists and intellectuals, as well as activists in Pakistan who protested the treatment of Bengalis in 1971.

“This is at the heart of Zakaria’s dilemma: how to narrate 1971 in a way that doesn’t lend itself to appropriation by the state (be it the Pakistani, Bangladeshi or Indian state)? ”

One of the challenges of studying these historical moments that hold so much potential for misappropriation is gathering “objective” narratives. When each individual experience is unique to a person, to a specific location, how do you tell an objective story? Personal narratives of 1971 are abundant, ranging from memoirs to published diaries to anthologies of interviews. What Zakaria very quickly discovers about this wide archive of narratives is that they can very easily be appropriated by the state to serve its own means, push its own agenda, and tell the story it prefers. This is at the heart of Zakaria’s dilemma: how to narrate 1971 in a way that doesn’t lend itself to appropriation by the state (be it the Pakistani, Bangladeshi, or Indian state)?

To do this, Zakaria attempts to interview people who have been pushed to the margins of the narrative of 1971 or forgotten completely, such as Biharis who remain in Bangladesh and are attempting to blend into the majority, but remain excluded on the basis of their ethnicity. To this end, she points out that the violence against Biharis perpetuated by the Mukti Bahini (Freedom Fighters) during the Liberation War, and particularly the events prior to March 26, 1971, have been all but forgotten in the popular Bangladeshi narrative. On the other hand, she examines the situation of Bengalis in Pakistan, some of whom were able to leave for Bangladesh during the war while others could not.

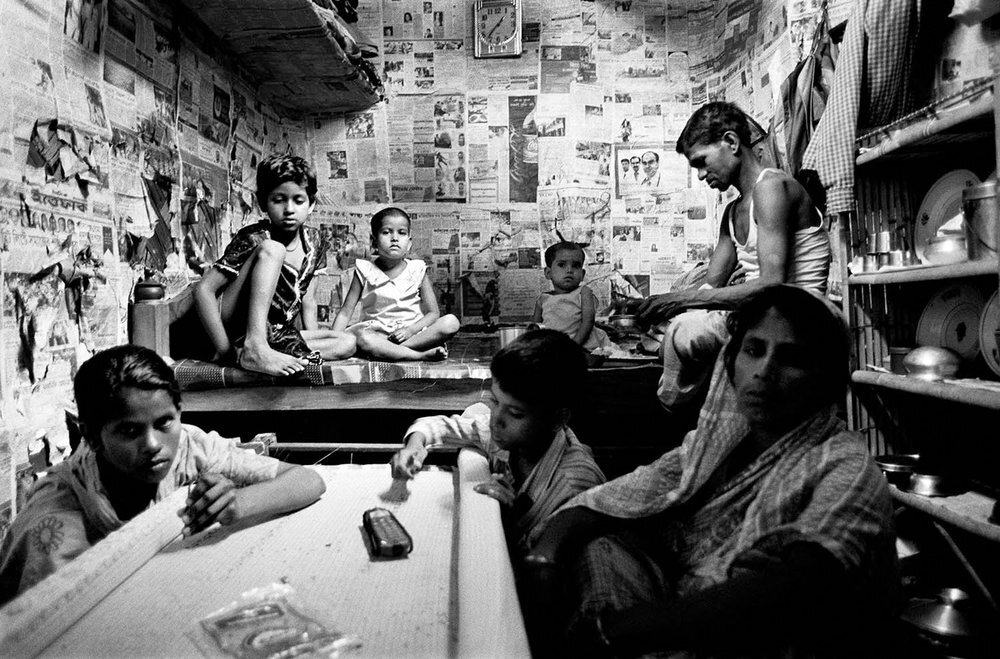

A Bihari family of seven works in their room in Kurmi Tola Camp in Dhaka. After 1971, Biharis were forced to settle in camps throughout Bangladesh. Source: No Where People

“An interesting takeaway from this book is the way in which it presents how contested the narrative around 1971 is even in Pakistan”

An interesting takeaway from this book is the way in which it presents how contested the narrative around 1971 is even in Pakistan. Since most of the literature on 1971 centres on Bangladeshi resistance, it was especially interesting to learn of the many grassroots movements in Pakistan which protested the war and the treatment of Bengalis. It is here that Zakaria’s interviews with activists and poets in Pakistan who led this movement produce a rich archive that begs to be explored more, and I certainly wish this was the focus of more than just a single chapter of her book.

But Zakaria's attempt to look at the stories of those traditionally excluded from the state’s narratives leaves many gaps to be considered. She discusses how the Pakistani state justified the war as an attempt to cleanse the “Hinduness” out of the Bengalis and therefore Pakistan itself. Surely then, there must be a lot to say about the status of the Hindu minority in Pakistan during the war? Instead, her focus on the two communities rendered “stateless” and seeking retribution — Biharis in Bangladeshi, Bengalis in Pakistan — fall into the trap of what we might call a liberal critique. This view holds that: these two states are the same because they treat these people in the same way. While it is true that neither state is innocent of perpetrating violence against minorities, to focus on the obvious ways in which it perpetuates this violence is uncreative and lacks nuance. It also caught my eye that, while Zakaria devotes significant time to a critique of the Bangladeshi state post-1971, the question of “stateless” citizens and minority rights in Pakistan rarely makes an appearance (barring a brief discussion of Bengalis in contemporary Pakistan). What makes Bangladesh’s treatment of “stranded” citizens so unique from Pakistan’s treatment of the Baloch, Biharis, or Muhajirs?

Refugees fleeing East Bengal in search of safety. Millions fled to neighboring West Bengal in India as the war with Pakistan intensified. Source: Raghu Rai via Dawn

“Yet, this does not seem like a story of understanding at all, as much as it reads like a narrativised absolution of guilt.”

Early in the book, Zakaria tells us that “this book is a Pakistani’s journey of learning [ . . . ] Bangladesh’s birth story through the oral histories of various Bangladeshis, Pakistanis, and some Indians” (p. xiv). Yet, this does not seem like a story of understanding at all, as much as it reads like a narrativized absolution of guilt. At a later point, Zakaria tells us how surprised students at a school in Bangladesh were by how “good” some Pakistanis could be and asked if they could hug her. She writes that “[she] did nothing more than have a regular conversation with them, but perhaps that is all we need to shatter the stereotypes we have of each other; a little interaction and some dialogue can go a long way in humanizing those we have learned to hate” (p. 300). Her use of the word “stereotype” here is interesting – Bangladeshis do not resent Pakistanis just because of a stereotype but because of a history of oppression and state-sanctioned violence directed against them.

The liberal vocabulary of “dialogue” and “humaniz[ation]” appears many times throughout the book, but Zakaria’s prescriptions end there. While she makes space for this dialogue to humanize, there is no clear indication as to where it will lead. Considering that Biharis in Bangladesh remain stateless to this day, that the rise of violence against minorities in Bangladesh and Pakistan continues, and the very fact that the state of Pakistan has yet to acknowledge (let alone make reparations for) the war, where does this dialogue lead us? Instead, Zakaria makes both herself — the Pakistani citizen who never learned and did not know any better — as well as Bangladesh’s minorities the objects of sympathy, not vehicles for imagining a political future constructed through transformative justice. What is the point of “understanding” and “undoing” if it does not lead to transformative change?

Another issue is with Zakaria’s methodology, especially the languages of her source material. Zakaria states very early on that most of her interviews in Bangladesh were conducted in English and a brief perusal through the sources listed in the book highlight that all of them are either in English or Urdu. While Zakaria’s attempt at trying to capture the voices of those who have been traditionally excluded from the narratives is admirable, one has to wonder to what degree she has full access to these narratives if she cannot consult the plethora of published personal narratives of the war, such as Sufia Kamal’s Ekattorer Diary, which are in Bengali.

“One has to wonder to what degree she has full access to these narratives if she cannot consult the plethora of published personal narratives of the war, such as Sufia Kamal’s Ekattorer Diary, which are in Bengali.”

There are also several moments in the book where Zakaria expresses her discomfort in certain situations and interactions and it comes out in rather interesting ways. For example, when she sits in the audience of Professor Harun’s speech in Dhaka where he goes on to express his disdain towards the treatment of Bengalis under Pakistani occupation, she writes “I want to remind him that I was born seventeen years after the war, but it holds no relevance. As a professor would later say to me, ‘We have nothing but hatred for you.’ I am, therefore, Pakistan; I am the Pakistan Army; I am Punjabi hegemony” (pg. 33). While she acknowledges her position as a Pakistani in Bangladesh, one has to wonder whether interjections such as these serve as an absolution or admonition of any lingering guilt that the author feels. Zakaria is quick to tell the reader how welcome or unwelcomed she, as a Pakistani, feels in these Bangladeshi spaces, but she does not always consider why that might be so in the first place.

Despite the shortcomings listed above, the book serves as an interesting primer for the uninitiated. It offers a robust view of the way in which the war of 1971 is remembered by and discussed in the states of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, and how it determines their relationship to one another through the frame of contemporary politics. The “gap” that this book fills within the research on the war is that it provides on-the-ground insight on the Pakistani side of the story, whereas studies of 1971 typically focus on the Bangladeshi perspective or takes a policy-based approach to the war. Perhaps in the future, researchers (or perhaps Zakaria herself) will take up the gauntlet to provide more context and analyses, but 1971 presents a very interesting archive that should be considered on its own merit.

Alif Shahed is a PhD student at the University of Toronto. You can follow him on Twitter at @alifsh__ as he searches for the perfect iced coffee